historical-objective vs. modernized-subjective interpretation

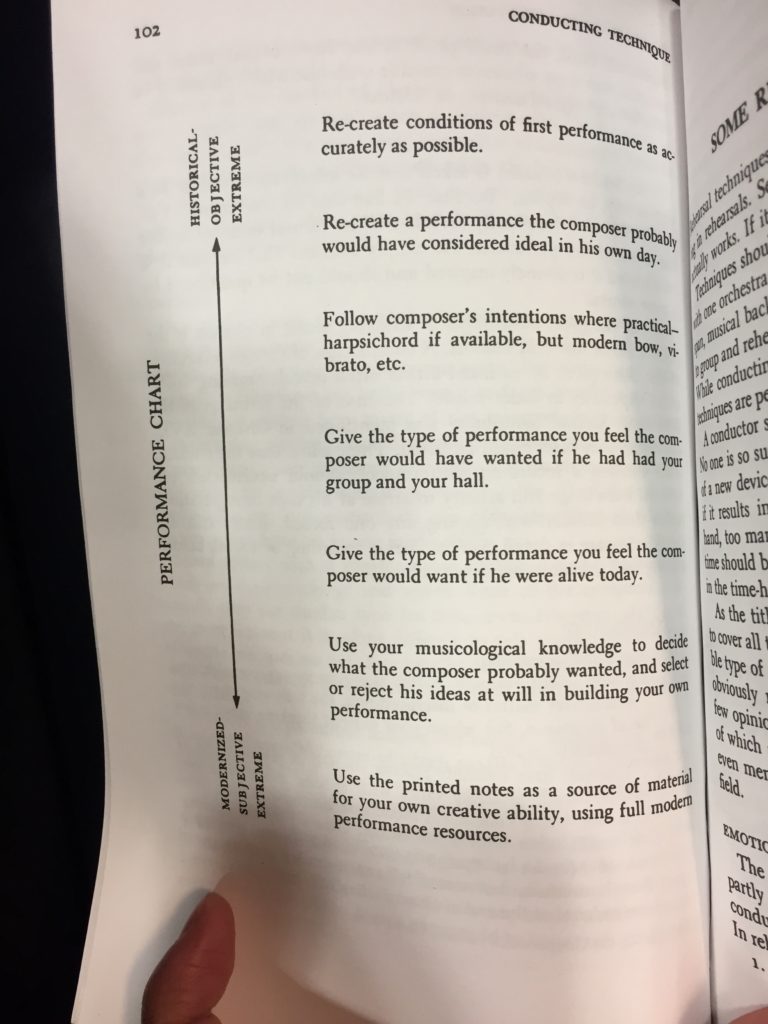

I came across the following chart in Brock McElheran’s text on conducting, Conducting Technique, and found it quite curious…

McElheran uses this chart to demonstrate one spectrum of values that could apply when you decide how to interpret a piece, and that a) being overly committed to the composer’s original time and place, or b) subjecting the composer’s work to personal whims, are both potentially dangerous. I think it’s a fair point.

Growing up, my piano teacher encouraged something closer to the modernized-subjective approach (“Use your musicological knowledge to decide what the composer probably wanted, and select or reject his ideas at will in building your own performance”). I still fall into this camp, though I’m learning to more carefully watch for the significance of the presence or absence of certain markings in the score as a way of listening for what could make the music most beautiful. But at the end of the day, if my aesthetic sense conflicts with what I think the composer wants, I usually choose my own desires over the composer’s.

I get the sense that much of the classical music world – at least, the orchestral/symphonic world – falls into a more historical-objective camp (“Re-create a performance the composer would have considered ideal in his own day”).

In contrast, the jazz and popular music worlds seem very much to have embraced the modernized-subjective approach (“Use the printed notes as a source of material for your own creative ability, using full modern performance resources”). Jazz is all about spontaneous improvisation on top of a theme. Pop music is rife with covers and fresh takes.

All this reminds me of a conversation I had with a new friend who’s a music director and pianist for musical theater productions in New York. Musical theater composers, he said, often care a lot less about whether you play specific notes, and more about whether or not the audience is affected in the way they intend…so there’s more room for improvisation there, too. Curiously, though, he also said that in musical theater, the composer is king. In the classical music world, I’ve heard it’s the maestro, not the composer, who’s king…

a bulrush basket

The brain appears to possess a special area which we might call poetic memory and which records everything that charms or touches us, that makes our lives beautiful… Their love story did not begin until afterwards: she fell ill and he was unable to send her home as he had the others. Kneeling by her as she lay sleeping in his bed, he realized that someone had sent her downstream in a bulrush basket. I have said before that metaphors are dangerous. Love begins with a metaphor. Which is to say, love begins at the point when a woman enters her first word into our poetic memory.

— Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being

I don’t like Kundera’s novels — I read The Unbearable Lightness of Being a few years ago and Ignorance just now, and these novels feel incomplete, unresolved — but there’s something about the poetry of his words that captivates the romantic part of my imagination. We have these poignant little moments in life, and this is what Kundera captures so well.

I went to see a new dentist earlier this week, and you forget this when you’ve had the same dentist for years, but a new dentist needs to diagnose what’s happening with your teeth all over again, so he takes your x-rays and tell you all these things you already know about yourself. That you had braces; twice, in fact, because your parents didn’t realize that having braces in elementary school was unwise. That you had your wisdom teeth taken out (three wisdom teeth; not two, not four, but three). That you still have a baby tooth — and this one you have to explain; you were born with an extra tooth on one side and one missing on the other, so they removed the extra adult tooth and pulled the one above it down with a gold chain, and the baby tooth never got pushed out and remains in your mouth to this day. It’s going to fall out soon, he says. Not tomorrow, but soon.

And suddenly, you are aware of your adulthood — not because you have a baby tooth, or because that baby tooth will someday soon fall out and you’ll either need an implant or have a missing-tooth smile for the rest of your life, but because you are the only soul in the world who knows about this baby tooth, and all at once it hits you, what it means to be alone.

That’s a Kundera moment.

being, but an ear

As all the Heavens were a Bell,And Being, but an Ear…

— Emily Dickinson

“Listening is something you receive,” my conducting teacher said, recalling this poem as I practiced conducting the beginning of Wagner’s Prelude from Tristan und Isolde. Fitting, now that I spend much of my days listening to and learning to create music. Fitting, too, that I am now rereading Difficult Conversations.

Thank you to Mark for inspiring this post.

the island of pleasure

Written in January 2011. Listen to the piece here, as recorded by Vladimir Horowitz.

…the aural work of Claude Debussy, musician of suggestion and atmosphere, not explicit emotion or story. If one perceives a song as a mirage only, how can one faithfully capture the music in words without involving assumptive interpretations? This is my challenge as I listen to Debussy’s “L’isle Joyeuse,” or “The Island of Pleasure.”

The first listen, eyes closed: This piece sounds like something I have known before—I have not heard it before, nor have I heard anything quite like it, but my soul feels a nostalgic familiarity. The experience seems like walking through a misty dream, or hearing the texture of soft white light. The trills, the escalation, and the dissonance create a tension that holds over me throughout the piece, never leaving until the very end.

The second listen, still eyes closed: The same musical ideas return over and over—the pervading trills and downward trios, the fleeting call and response, the passionate melody—but each time, they are new again. Yet, they are new not because of the modulations, nor is it the dynamics, nor are these musical designs returning in the way a pop song cannot stop repeating itself. Once heard, the ideas—not the notes, but the inkling of the tension their pattern once caused—are more powerful the second time, the louder time, the time it appears in a different key, but not because of those facts. How is a repeated idea new, but not because of what makes it different, but because it is repeated, which should make it no longer new?

The third listen, eyes open so I can record what I feel, section by section: There are suspenseful trills and trios, graceful and playfully light ups and downs, dissonance with harmony, elevating motions, grand arpeggios across the keys. The glorious breakthrough of the melodious theme, consonant yet uncertain, mellifluous, surreal. This music makes me want to move; this music moves me. Dissonant reprises, sprinting scales, spinning out of control to a sudden STOP, then a steady growth. A glorious culmination—intense warmth, then a chill, runs through my body as the poignant theme returns, the jarring 5-on-3 rhythm of mismatched notes only adding to the magnificence. As in a pas de deux,¹ with a man’s powerful whirling grand jetés across the dance floor, sweeping the lady into a motion that spirals outward to the universe. Finally, return to the tensive trills, tremolo, crescendo, accelerando, expand—and done.

The fourth listen, viewing the musical score: Debussy demands the impossible of his performer. How can one articulate piano, piu piano, and pianissimo—differences in volume that the human ear can barely perceive?² The interpreter must use his own judgment to let the dynamics expand beyond the given narrow range, if he wishes to convey the full color of the piece’s dynamic tensions.

The fifth listen, eyes closed again: The middle melody, bold yet wistful, is an altogether different species from the main themes. Do you know the precious feeling of waking up beside your lover? The gentle smile, the tranquil rays sifting onto the sheets, treasured in his arms, an internal yet explosive passion? That is how the melody cherishes me. In movies, there is a romantic image of running downhill through a large grassy field, the wind through your hair like silk on your skin…this characterizes the post-melody. And now, imagine the desire for an idealistic, eternal love fulfilled. This love seems but an illusion, for love is mercurial, complex, vague; the rapid repetition of motifs perhaps exudes apprehension, anxiety, tension; the confusion we find when enveloped by love; the surprise color changes, like the sudden march-like major chords leading to the climax, might capture love’s vicissitudes; the tender singing voice of the second theme captures the high of being one with one’s love. “L’isle Joyeuse” could be a snapshot of the turbulent emotions of love, both the reality and the dream, both the insanity and the reason.

The sixth listen, now paying particular attention to contrast, in order to explore how Debussy manipulates the tension: he fills his work with contradictions: the juxtaposition of grating trills with playful up and down arpeggios, and of cacophonous note mixtures with smooth, measured melody; the coexistence of consonance and dissonance, superimposed rhythms; uplifting brilliance contrasting with quietude; lack of definite scale or scheme, surprise bursts throughout. “L’isle Joyeuse” inspires in me an overall sense of happiness and peace, but deep and jumbled feelings. Debussy calls it an “Island of Pleasure,” but much of the piece is particularly intended to sound discordant and tense, if not unpleasant. The pleasant and unpleasant exist alongside, swapping roles of harmony and melody, articulation and dynamics, rhythm and speed: the sweet melody of the second theme is placed with bitter rhythm, the violent harmonies leading up to the climax are paired with classical-style swelling of both loudness and velocity.

The seventh listen: Music of the classical and romantic periods established the norms for evoking emotions: the minor key is for doleful nocturnes, the major key for grand, sweeping pronouncements of delight. Debussy, however, does not commit to any key for his description of pleasure; he even uses the blindingly positive major chords of C and Eb for a fleeting two measures each to rudely interfere with the recapitulation’s dissonant chaos. Until the finish, Debussy never entirely relieves the listener from musical tension; he allows dissonance to give way to consonance, or halts the countless reiterations, or lets the voice to descend to lower pitches, but never all at the same time. To describe his pleasure, Debussy instead seems to capture the stress that comes before it. Indeed, right after the final appearance of the melodious theme, the dissonant chaotic repeats itself again and again until there is resolution to the tonic chord, and the mind can relax. However, the pleasure is not only at the conclusion, but throughout; the powerful melodic theme, the mischievously swinging ups and downs, the haunting trills, still linger in the mind after it is done and the pleasure is gone. One finds pleasure in the process of achieving pleasure, yet this process is riddled with what is not purely pleasurable. To evoke pleasure, one necessarily searches for the displeasure, the stress, the tension; and only with that contrast does one find joy.

Footnotes

1. In ballet, a duet performed by the principal male and female, often in a romantic context.

2. piano is Italian for ”soft” in volume; piu piano and pianissimo are both Italian for “very soft.” Because piano and pianissimo are the standard dynamic markings for volume, and because piu piano is used only relative to piano, the pianist typically infers that piu piano is louder than pianissimo, but only negligibly so.

the relationship ratchet

A ratchet is a mechanism that allows for motion in one direction only. (Here’s a video that demonstrates how this works.)

Why is it so difficult to dial back an already deep relationship?

- When we want to deepen a relationship, we make ourselves vulnerable, because we will hurt if we learn that we care more about someone than they care about us. We celebrate conquering this fear. We accept that love requires a leap of faith. We believe it’s healthy to build our rejection stamina.

- When we want to dial back a relationship, we make them vulnerable, because they may hurt if they learn that we care less about them than they care about us. We denounce people who take advantage of other people’s vulnerabilities as manipulative and mean.

Naturally, there’s the anguish of breaking up with a significant other, as well as the pain of severing ties with one’s family. When it comes to friendships, however, we’re seldom explicit about dialing them back – perhaps because the commitment we make to each other as friends is often less well-defined.

Instead, we let our friendships peter out, dwindle away. We tell ourselves that we do this because it might be less painful to the other party if the change is gradual. Realistically, that’s often true, but alas – it’s usually least true when it matters most.

Thank you to Albert for inspiring this post.

kilimanjaro

Preparations

- Select a route. We chose the 8-day Lemosho route in order to avoid altitude sickness and optimize for summit success rate.

- Shape up. For true mountaineers, Kilimanjaro isn’t a difficult climb, as it doesn’t require much specialized training, technique, or gear. For a “person of average fitness,” the climb is doable, but certainly not easy.

- Altitude. The main challenge – aside from the sheer determination needed to keep your body moving through a cold and snowy summit night – is the altitude. Kilimanjaro’s summit is 19,341 feet high, or about two thirds as high as Everest. Up top there’s only about half as much oxygen as there would be at sea level. Take medicine (Diamox) to help with acclimatization, but otherwise all you(r guide) can do is climb slowly and control your elevation carefully so your body can naturally adjust to the lower oxygen content.

- Contrasting climates. Over the course of a week, you’ll progress past farms and forests, up through heather & moorland, across highland desert, and into arctic conditions. And then you’ll come all the way back down.

- Meditation. Altitude trekking for the unacclimatized is slow, plodding, and ultimately meditative. Bring mental spaces you’d like to mull over.

Humble pie

- Tempo. The speed record for a summit and return is 8 hours. (Compare that with 8 days.)

- Competence. A group of 6 climbers warrants 23 staff – 1 head guide, 2 assistant guides, 2 cooks, and the rest porters, who carry everything that isn’t in your daypack: your bags, the sleeping tents, a mess tent + table + chairs, food + cooking gas + equipment, a toilet. The staff travel at least twice as quickly while carrying at least twice as much. (We asked one of our guides if there was any training or physical exam to be a porter, and he laughed. “They are African,” he told us. It seems that most folks there grow up carrying heavy loads on their heads, developing that kind of physical stamina as part of the natural course of life.)

- Energy. A couple of the porters are “summit porters” who go with you and the guides to the summit, so that there are enough people to carry down any emergency evacuees. When your energy starts to fade, they sing and clap the energy back into you.

Learning

- Endurance. You can keep going much further than you think you can.

- Community. Trustworthy guides and caring compatriots share their strength.

grave of the fireflies

i can’t stop thinking about this movie

belonging & conformity

According to Baumeister & Leary’s research on belonging:

Belonging is closely related to group membership, and thus with the concept of conformity. Unsurprisingly, failing to conform is an obstacle for the feeling of belonging. Whether by choice or by chance, those of us who are different from the group are less likely to feel like we belong with that group.

I haven’t stopped yearning for the psychological safety of strongly belonging to one group, but I’ve also accepted that few groups if any truly capture my essence, because I cherish my own uniqueness and the beliefs I passionately hold. Belonging comes from a few strong one-on-one relationships, and from organizations that I care for but that don’t fully define me and in which I don’t always feel like I fully belong (and that’s okay).

For me, this is what it means to be an individual. For me, this is what it means to be an independent self.

scientific approaches to striving for happiness

Many of our strategies for happiness come from anecdotal evidence from our own lives or from friends’ recommendations. What happens when we apply a scientific lens to the art of striving for happiness?

Approach 1: Chemical Analysis

Scientific studies demonstrate that 1) the presence or absence of specific chemicals corresponds with different emotional states, and 2) actions can change the presence or absence of such chemicals. Based on my hacky research,* here are some actions you can take that have been shown to positively affect your happiness chemicals:

*Researching these chemicals was more complicated than I expected. Many popular media articles reference these chemicals but don’t cite sources for their statements. I opted neither to rely on these articles, nor to do a rigorous review of the scientific literature; rather, I looked to make claims substantiated by at least one or two reasonably reputable sources, such as abstracts of peer-reviewed scientific papers or articles from well-respected scientific news outlets, to form these conclusions.

Endorphins

- Humans knew about opium & morphine before we knew anything about endorphins. “Endorphin” is a portmanteau of “endogenous” and “morphine,” meaning morphine that originates internally.1

- Endorphins work by binding to opioid receptors that 1) cause a cascade of interactions that inhibits the release of a key pain transmission protein, and 2) release a neurotransmitter that results in excess dopamine.2

- Exercise is commonly linked to higher endorphin levels. Contrary to popular belief, however, endorphins are probably not responsible for “runner’s high.” Endorphins have been shown to take more than an hour to increase, and have also been shown not to cross the blood-brain barrier, making it unlikely that they are responsible for exercise euphoria.3, 4

- I already knew that eating chocolate makes me happy, but apparently it’s not just the taste – eating chocolate triggers the release of endorphins, too.6

Dopamine

- Dopamine enhances our expectations of pleasure.7 When faced with the choice of a low-effort low-value reward vs. a high-effort high-value reward, higher dopamine levels make you more likely to choose the higher-effort and higher-value reward.8

- Dopamine also has been shown to improve working memory and better selection of goal-directed actions (i.e. focus).9

- Pleasurable experiences like food and sex cause dopamine hits.10 “Peak emotional moments” in music

- There aren’t specific scientific studies for this, but a lot of popular media articles suggest that you can game your own dopamine systems by accomplishing smaller tasks or breaking down a large goal into small pieces in order to trigger smaller dopamine hits along the way.

- Beware: Dopamine is addictive. Also, know that more dopamine is not by itself sufficient for more motivation; dopamine needs specifically to be increased in the reward & motivation center of your brain in order to motivate you. “Slackers” also have elevated dopamine levels, just in other areas of their brain.12 While not backed by scientific literature, my guess is that dopamine reinforces past behaviors, and you have to be careful to only reinforce the behaviors you want to keep.

Serotonin

- Serotonin has been shown to have a bounty of positive effects: biasing people toward having more positive emotional responses to situations (rather than directly affecting mood), reducing aggression and increasing desire for cooperation and good will toward others, and engendering “a calm yet focused mental outlook.”13, 14, 15

- Thinking of happy or successful memories, experiencing social success or high social status, exposing oneself to bright light, eating carbs, drinking alcohol non-chronically, and exercising have all been shown to boost serotonin levels.16, 17, 18

- Popular media often seems to indicate that low serotonin levels cause depression, and that increasing serotonin levels can thus cure depression. However, this claim has not been clearly substantiated. What we do know is that impairing serotonin function can sometimes cause clinical depression, low serotonin function may impair recovery from depression, and serotonin-based drugs do bias people toward more positive emotional responses (as mentioned above).19

Oxytocin

- Originally perceived only as a facilitating hormone for labor and breastfeeding, oxytocin has since been embraced by popular media as the “cuddle hormone.” Increased dosage of the drug has been found to increase trust in games, improve monetary generosity, improve people’s ability to infer emotional state from subtle expressions, increase time spent gazing at a face’s eye region, and make happy faces more memorable.20, 21, 22, 23, 24

- Oxytocin appears to promote monogamy for people in monogamous relationships: it leads men in relationships to avoid approaching single women, and leads people to perceive their partner’s touch as especially pleasant while perceiving a stranger’s touch as especially diminished in quality.25, 26

- Oxytocin may also drive conformity. People with additional oxytocin are more likely to follow a charismatic leader, and are more likely to promote the in-group over the out-group.27, 28

- Frequently hugging your partner, orgasming, getting a massage, and petting your dog have all been shown to increase oxytocin levels.29, 30, 31, 32 Singing lessons and improvised singing have been shown to increase oxytocin levels as well.33, 34

- Contrary to what many popular media articles say, I have found no evidence that hugging or touching someone who is not your partner increases oxytocin levels. Nor have I found any evidence that giving gifts or money will increase your oxytocin levels; I have only seen studies showing that people with high oxytocin levels are more generous. This is not to say that hugs and generous gifts are a bad idea or that they won’t make you happy, just that I have not found a peer-reviewed study demonstrating that these activities will naturally increase your oxytocin levels.

A few other chemicals that affect happiness that I won’t go into at this time: adrenaline & noradrenaline, cortisol, endocannabinoids, GABA…

Approach 2: The Scientific Method

The scientific method is the process by which humanity aims to get to an accurate representation of the world. Very briefly, the idea is that when you go about looking for answers in the world, you should 1) form a hypothesis or prediction for how the world works, 2) run experiments testing that hypothesis, and 3) analyze the results in order to draw conclusions. If your experiments aren’t conclusive, you go back to the drawing board, modify your original hypothesis, and the cycle begins again.

It turns out you can apply this to life, too. Basically, 1) write down a hypothesis about what makes you happy, 2) try doing those things, and then 3) analyze how you felt about doing them and decide whether you want to keep doing them.

This is, of course, an oversimplified approach:

- Some things require expertise or time before becoming likable. We often like things more after we understand them or have become good at doing them, and building skill and understanding takes time. You’ll need to be thoughtful about how you set up your “experiment” to account for that.

- This approach is also somewhat biased toward valuing in-the-moment happiness while you’re doing the work over the retrospective happiness you gain after hitting a milestone or accomplishment. Again, experiment design, particularly the length and ending conditions of the experiment, is key.

- Finally, your preferences and values will change over time. You may not like Brussels sprouts today, but you might change your mind in five years. You might enjoy working on engaging assignments at work today, but decide in a few years that you want to do work with a stronger social impact mission, even if it’s less interesting day-to-day. There’s not much you can do here, other than allowing yourself to edit what you know about yourself as time goes by, and acknowledging that some experimental results won’t apply forever.

There will be times when we’re actively running experiments, are impatient to know the results, and need to counsel ourselves to stay the course. But if you don’t currently have a promising active experiment, instead of allowing indecision about your life direction to freeze your activity, try coming up with a possible career path you could be interested in, and figure out a way that you can validate whether you would actually enjoy having that career. Can you talk with 5 people in career x about what their days are like and what they love and hate about their work? What is a side project version of career x you can take on? You need to actually run experiments in order to learn more about yourself and the world. If you don’t know what you want, try something.