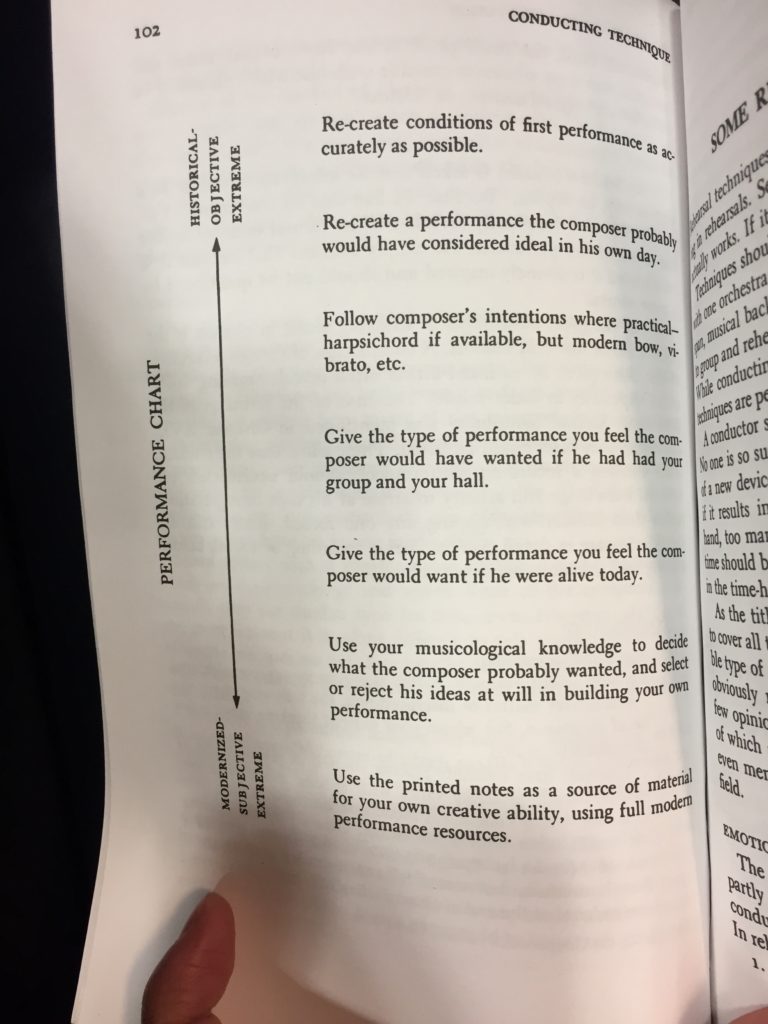

I came across the following chart in Brock McElheran’s text on conducting, Conducting Technique, and found it quite curious…

McElheran uses this chart to demonstrate one spectrum of values that could apply when you decide how to interpret a piece, and that a) being overly committed to the composer’s original time and place, or b) subjecting the composer’s work to personal whims, are both potentially dangerous. I think it’s a fair point.

Growing up, my piano teacher encouraged something closer to the modernized-subjective approach (“Use your musicological knowledge to decide what the composer probably wanted, and select or reject his ideas at will in building your own performance”). I still fall into this camp, though I’m learning to more carefully watch for the significance of the presence or absence of certain markings in the score as a way of listening for what could make the music most beautiful. But at the end of the day, if my aesthetic sense conflicts with what I think the composer wants, I usually choose my own desires over the composer’s.

I get the sense that much of the classical music world – at least, the orchestral/symphonic world – falls into a more historical-objective camp (“Re-create a performance the composer would have considered ideal in his own day”).

In contrast, the jazz and popular music worlds seem very much to have embraced the modernized-subjective approach (“Use the printed notes as a source of material for your own creative ability, using full modern performance resources”). Jazz is all about spontaneous improvisation on top of a theme. Pop music is rife with covers and fresh takes.

All this reminds me of a conversation I had with a new friend who’s a music director and pianist for musical theater productions in New York. Musical theater composers, he said, often care a lot less about whether you play specific notes, and more about whether or not the audience is affected in the way they intend…so there’s more room for improvisation there, too. Curiously, though, he also said that in musical theater, the composer is king. In the classical music world, I’ve heard it’s the maestro, not the composer, who’s king…